When most people envision the cannabis plant and its powers, chances are the first thing that leaps to mind is a cannabis leaf. Even those who have never seen an actual cannabis plant, ingested any cannabinoids, or been in a college dorm room, will recognize those seven serrated leaves from a million sightings on beanies, lighters, bumper stickers, and anywhere else people can proclaim their love of cannabis, rebellion against the establishment, or belief in individual freedoms, reggae, psychedelics, counter culture, or natural medicine.

But for anyone looking to find the true heart of what makes cannabis such a cultural and therapeutic behemoth, they’ll find the magic not in the symbolic leaf, but in the far less-recognizable, microscopic trichome. That clear little mushroom-shaped gland on the outside of the plant contains all the cannabinoids (like THC and CBD), terpenes, and flavonoids that make cannabis the uniquely powerful plant conjured by its unofficial leaf logo.

Plant Power

The word trichome comes from the greek word trikhoun, meaning “covered with hair,” and throughout the last two centuries has been used rather generically as any outer hairs, glands, scales, or other little outgrowths found on plants, algae, or lichens. Most cannabis trichomes are of the gland variety, and they grow only on the outside of the plant, but especially around the reproductive parts of unfertilized females (the buds). While they are found to some extent on the leaves themselves, the stereotypical cannabis leaf doesn’t have a lot to offer in terms of medicinal or psychoactive effects.

If you’re familiar with cannabis in its flower form, you’re familiar with a sticky, frosty layer that covers the buds and some leaves. Maybe you’ve even looked at it through a microscope or loupe, and seen the little glands that protrude from the plant’s surface like a clear mushroom forest. But are they all the same? What do these glands do, and why does the cannabis plant make them? These are important questions, since it’s these glands, known as trichomes, that contain all the chemical magic of this incredible species.

Bulbous, Sessile, and Stalked

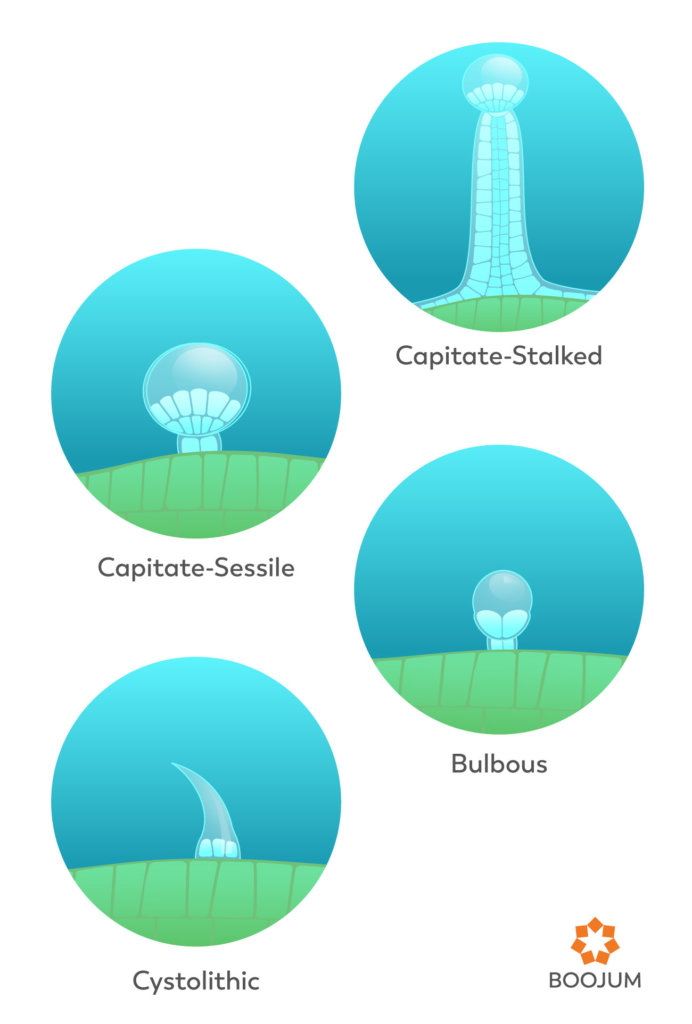

Glandular trichomes in cannabis come in four different varieties. Bulbous trichomes are the least common and smallest, at just 10-20 microns long, and are connected to the plant by a double celled stalk. Almost invisible, but giving the plant a crystal sheen, bulbous trichomes are distributed on all aerial surfaces of the plant, and while there isn’t a definitive answer yet on what chemical compounds they do produce, there is no evidence that they produce cannabinoids.

Capitate-sessile trichomes, also just called sessile trichomes, are the middle of the pack in terms of both size and distribution. They average around 50 microns across, or five times as large as bulbous trichomes. They’re named sessile (latin for “sitting”) for their lack of a stalk, though they do have a single cell that functions as a stalk, hidden from view under their glandular head. Like the larger stalked trichomes, sessile trichomes secrete and store cannabinoids and terpenes. Recent studies suggest that sessile trichomes on the female reproductive anatomy (like the buds) grow into the larger stalked trichomes—so their smaller size and single-celled stalk are most likely features of immaturity rather than a different category of trichome.

Capitate-stalked trichomes (also referred to simply as stalked trichomes) carry the mother lode of THC, CBD, and all the other cannabinoids, terpenes, and flavonoids that make the cannabis plant such an influential species. These look like clear mushrooms with long stalks, and are found almost exclusively on female plants, mostly around the calyces and bracts—essentially the cannabis buds. They are now considered the mature version of the sessile trichomes, having doubled in size, and grown a multicellular stalk.

While stalked trichomes are found primarily in female plants, male plants have their own trichomes too — antherial glandular trichomes, which are found only on the anthers (the part of the plant where pollen is produced). While they’re just a little smaller than the female’s stalked trichomes, antherial trichomes are far less abundant, and are not thought to contain cannabinoids.

And finally, non-glandular trichomes, called cystolithic trichomes, are also found in cannabis. Primarily grown on the leaves, they are thought to reduce palatability to animals that might otherwise eat them.

What’s in a trichome?

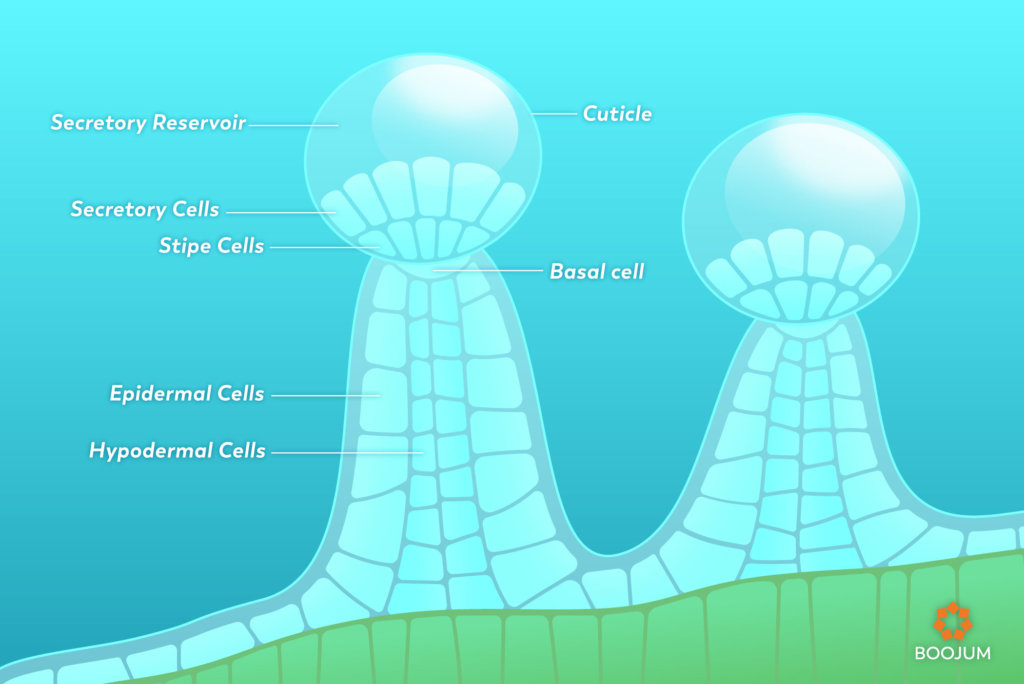

Most cannabis connoisseurs can tell you that a thick frost on the buds is a good sign, translating to potency. That’s because trichome heads, called secretory reservoirs, are essentially metabolite storage cavities, and the larger and more numerous the heads, the more THC, CBD, or CBG the plant will have (not to mention terpenes). Both sessile and stalked trichomes have a little disc of secretory cells that produce metabolites (like cannabinoids and terpenes), which are then released into the head, where they are stored, or turned into other molecules.

While it’s clear that cannabinoids and terpenes are made in the trichomes, there is still some uncertainty as to how it all goes down. The most current research suggests that the cells in the secretory disc are responsible for making CBGA and terpenes, and releasing them into the secretory reservoir. It’s here, floating around in the head of the trichome, that the CBGA encounters the enzymes that will change some of those molecules into THCA, CBDA, CBCA. Those enzymes determine the cannabinoid ratio of each trichome, plant, and chemovar.

In the early stages of development, secretory cells are hard at work creating the molecules that will fill up the storage cavity. The head swells as more and more molecules are secreted into the cavity. Trichome head colors change depending on what is inside them, starting out clear, then becoming more and more opaque, eventually passing their prime and turning a reddish brown color. As THC decays into CBN, the darker the heads become.

Trichome Evolution

It’s thought that plants evolved to produce trichomes in order to help guard against predation. Many terpenes are antimicrobial, antifungal, and insecticidal, as well as being sticky and oftentimes bitter—all good properties for keeping pests at bay. Some cannabis pests, like aphids and thrips, emit alarm pheromones. So when they are mired in a sticky terpene forest, chances are individuals will warn their fellow insects to steer clear, and discourage a more extensive attack.

Trichomes also offer physical barriers that may help in cannabis survival. Cystolithic trichomes are scattered over the surface of leaves, making them an uncomfortable snack. All types of trichomes help to trap a layer of air on the surface of the plant, protecting against cool drying winds, and reflect certain light wavelengths, protecting against potentially damaging infrared and ultraviolet spectra.

Even a small advantage can help in the evolutionary arms race, and trichomes conferred enough benefit to cannabis survival as to be naturally selected for. When humans stepped in, we realized the benefit of this trichome-covered species, and helped it evolve further by breeding the plants that held the most potent medicine.

Trichomes Everywhere

Take a look at a cannabis bud under a microscope, and you’ll see trichomes. Kief is just loose trichomes. FSO and CBD oils are the result of dissolving trichomes and extracting the molecules within. Solventless rosin is made by knocking trichome heads from the stalks by agitating them in water, then collecting and pressing them. All forms of processing cannabis for medicine involve processing the trichomes, since they are the only part of the plant with cannabinoids and terpenes. And we think it’s pretty magical that these clear little mushroom-shaped glands have evolved in a way that lets us harness their potent powers.

Resources

Ebersbach, P., Stehle, F., Kayser, O., & Freier, E. (2018). Chemical fingerprinting of single glandular trichomes of Cannabis sativa by Coherent anti-Stokes Raman scattering (CARS) microscopy. BMC plant biology, 18(1), 1-12.

Livingston, S. J., Quilichini, T. D., Booth, J. K., Wong, D. C., Rensing, K. H., Laflamme‐Yonkman, J., … & Samuels, A. L. (2020). Cannabis glandular trichomes alter morphology and metabolite content during flower maturation. The Plant Journal, 101(1), 37-56.

Potter, D. (2009). The propagation, characterisation and optimisation of Cannabis sativa L as a phytopharmaceutical (Doctoral dissertation, King’s College London).

Sirikantaramas, S., Taura, F., Tanaka, Y., Ishikawa, Y., Morimoto, S., & Shoyama, Y. (2005). Tetrahydrocannabinolic acid synthase, the enzyme controlling marijuana psychoactivity, is secreted into the storage cavity of the glandular trichomes. Plant and Cell Physiology, 46(9), 1578-1582.